Cybersecurity Industry Report: Planning for Failure in Security Softwares That Cannot Be Taken Offline

Most of the world runs on software you never see. The kind that sits inside computers all day and all night, watching, checking, protecting.

Yashika Vahi

Community Manager

Table of contents

Share

In big corporations—airports, hospitals, banks, universities—every computer has a small program installed on it whose only job is to stop bad things from happening. It watches for hackers. It looks for strange behavior. If something looks dangerous, it blocks it and reports back to a central control room.

Think of it like a security guard who never sleeps and never asks questions. These programs are called endpoint security sensors.

They are always online.

They are deeply trusted.

And they are not optional.

To make this possible, companies accept a deal—usually without thinking about it too much:

We will give up control of individual computers

so that one central system can protect everything.

That’s why these tools are allowed to update themselves automatically, why they’re allowed deep access and why they change often, quietly, in the background. And everyone shares the same comforting belief: If something ever goes wrong, it will be caught quickly, fixed quietly, and nobody outside the IT team will ever know.

On July 19, 2024, a cybersecurity company called CrowdStrike sent out what looked like a routine update.

CrowdStrike makes a product called Falcon. Falcon is used by some of the largest organizations in the world—airlines, hospitals, banks, government offices. It works by installing a small program on every computer in the company. That program quietly watches the computer all day and all night, looking for signs of hackers or dangerous behavior.

Most people never see it.

But their entire job depends on it working.

That day—July 19, 2024—CrowdStrike released a normal Falcon update. Nothing dramatic.

No rush. No emergency. The update was meant to improve protection. That’s it.

Inside the update was a new set of instructions. You can think of it like a checklist:

“Look at these things.

If you see them, react.”

This kind of update happens many times a day. Companies allow it because they trust CrowdStrike to keep them safe—and because stopping hackers requires constant change.

The problem was small. Almost silly. The checklist asked Falcon’s software to look at 21 things. But the Falcon software running on computers only had 20 things available. That’s all.

During testing, this mistake stayed hidden. The missing item existed on paper, but the software never actually had to examine it closely. So nothing broke in the lab.

Then the update reached the real world. And for the first time, Falcon actually tried to look at the 21st thing. It reached for something that wasn’t there. And when it did, it broke.

Many computers crashed while starting up, and then couldn’t start again at all.

Now here’s where the story turns dark. CrowdStrike noticed the problem and stopped the update within about an hour. But by then, it was already too late. Because Falcon runs on hundreds of thousands of computers across the world. Many of them had already downloaded the update automatically—exactly as designed.

Some computers were stuck in endless restart loops. Some couldn’t fix themselves at all. Rolling back the update didn’t help—because the computers couldn’t even turn on properly to receive the fix. Fixing them now meant manual help. One by one. Flights were delayed. Hospital appointments were postponed. Payments slowed. Customer support systems went dark. Entire organizations were forced to fall back to pen and paper because the tool designed to protect them had failed.

Conclusion : What Cybersecurity Product Planning Must Look Like Next

When a single update can reach hundreds of thousands of machines in minutes, failure is no longer a local event. It becomes systemic.

Blast-radius engineering

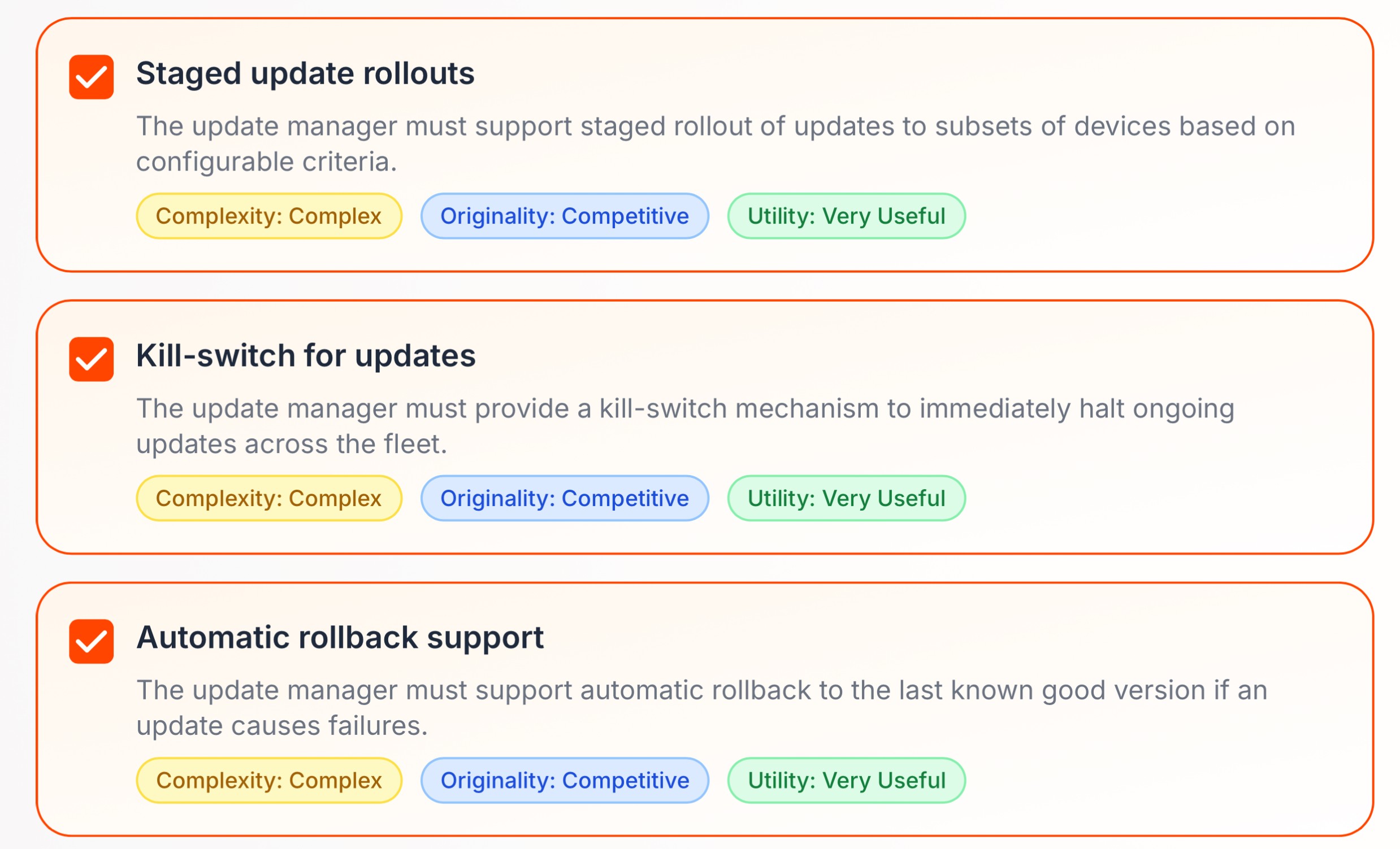

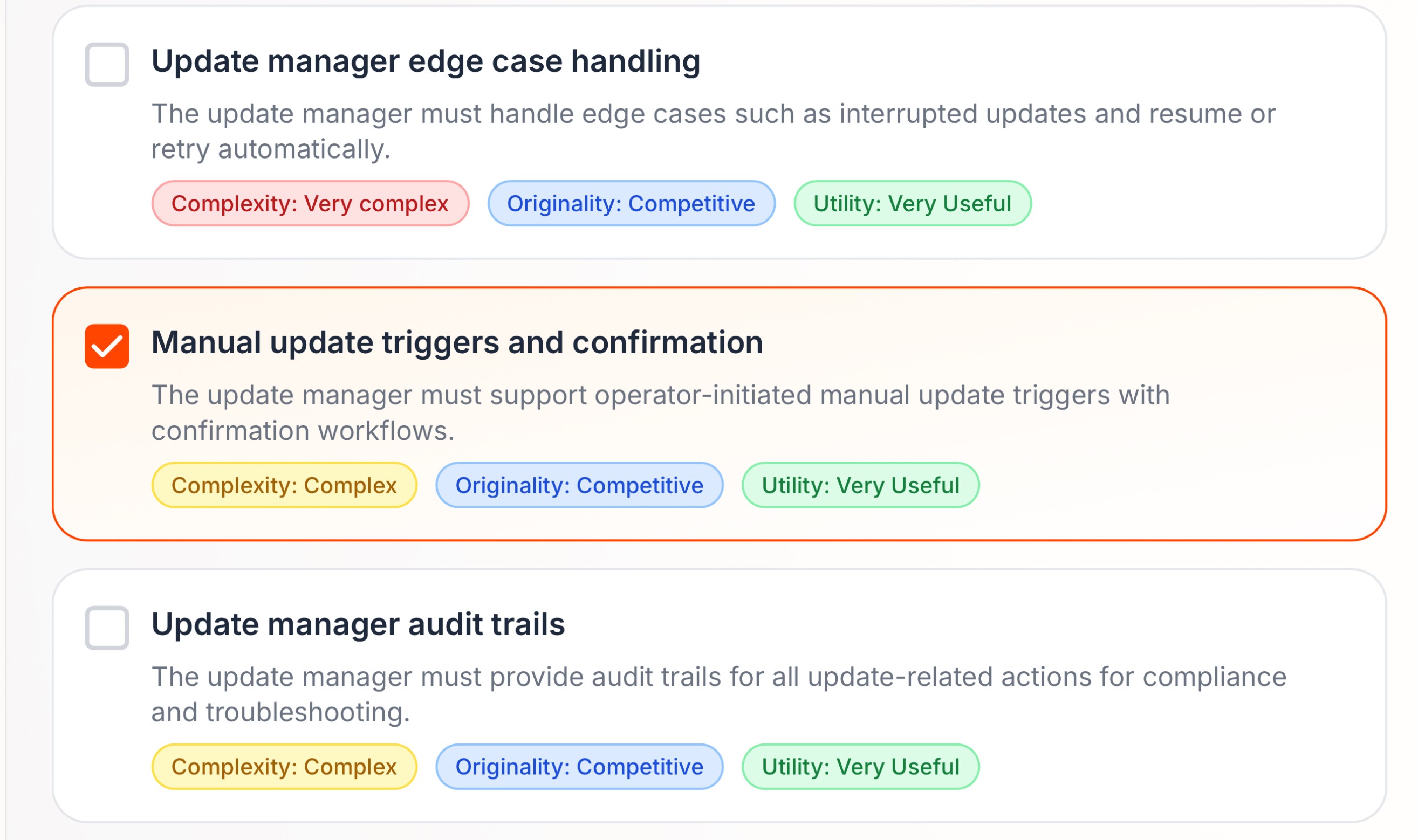

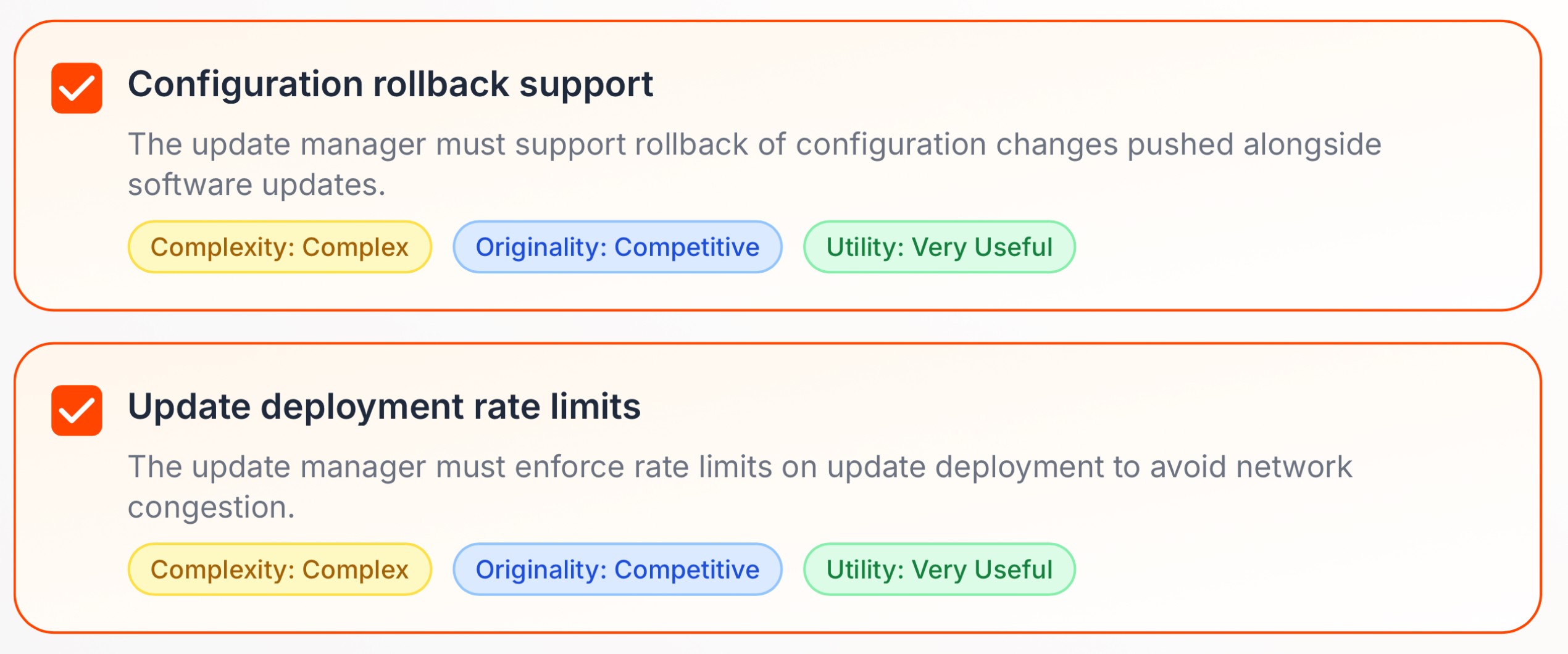

This is where blast-radius engineering becomes a product decision. Updates must be designed so they physically cannot reach everyone at once. Staged rollouts, automatic canary groups, rate limits, and region-by-region expansion aren’t “best practices”—they are safety barriers. If the first small group fails, the system must stop itself before the rest of the world ever sees the change.

Hard recovery design

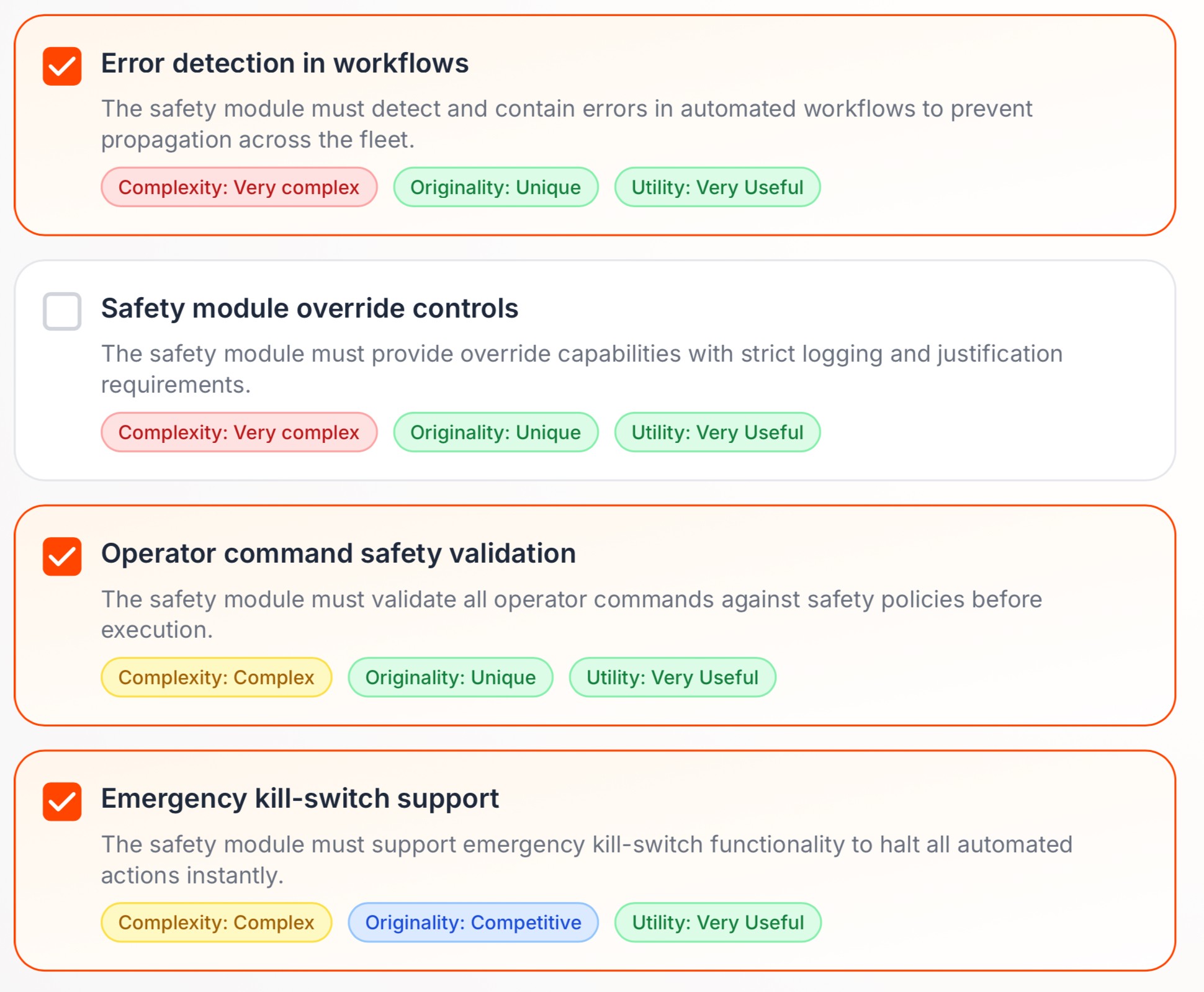

The CrowdStrike failure showed this clearly: stopping the update was fast, but recovery was slow and manual. That means cybersecurity planning must include hard recovery design from the start—immediate revoke capabilities, a known “last good state,” and practical offline recovery paths for machines that cannot even boot.

Treat content as executable logic

At the heart of the failure was something even more basic: a broken contract between content and runtime. The update expected one thing; the software provided another. Future cybersecurity products must treat content as executable logic. That means strict contracts, validation that reflects real runtime behavior, and safety checks that fail quietly instead of crashing operating systems.

Rigorous real-life testing

Testing also has to change. The CrowdStrike update passed tests because the tests didn’t resemble reality. Wildcards masked the dangerous path. In production, the system had no such protection. Cybersecurity products must be tested the way they are actually used—under weird, hostile, and adversarial conditions. Every field must be exercised. Unexpected inputs must be normal test cases. If a path can be reached in production, it must be tested on purpose.

This is where ArtusAI fits into the picture. Our tool isn’t about adding more features to cybersecurity products. It’s about helping teams plan systems that remain controllable when things go wrong. Planning that makes assumptions explicit. Planning that limits blast radius by design. Planning that treats recovery, disagreement, and failure as first-class concerns. Because once an update is live at global scale, there is no planning left to do. The outcome is already locked in. The difference between a contained incident and worldwide disruption isn’t better code. It’s better planning—done early, deliberately, and with failure in mind.