When a Helper System Takes Control: What the Aerospace Industry Really Teaches Us About Software Planning

How did an ambition to quickly meet market demand end up costing more than three hundred lives?

Yashika Vahi

Community Manager

Table of contents

Share

Competing With Airbus: How Software Was Used to Mask a Hardware Shift in the 737 MAX airplane

Imagine you’re riding a bicycle. Sometimes, when you go fast or hit a bump, the front wheel wants to lift up. So someone adds a small helper. It doesn’t take over the bike. It just nudges you back when you lean too far.

That’s how MCAS was supposed to work. On the Boeing 737 MAX airplane, MCAS stood for Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System. A long name for a simple idea:

“If the airplane’s nose starts pointing too high, gently push it back down.”

Boeing built the 737 MAX to compete with Airbus’s A320neo—a fuel-efficient airplane airlines loved. To save fuel, Boeing installed larger engines. Because the plane sits low to the ground, those engines had to be mounted higher and further forward.

That small change caused a new behavior: in rare situations, at steep angles, the plane wanted to tilt its nose upward more than older 737s.

Airlines wanted pilots to fly the MAX like older 737s. Regulators wanted it to behave like older 737s. Boeing wanted fast certification and minimal retraining. So MCAS was added.

Quiet. Invisible. Rarely active.

A helper.

The airplane had two sensors that measured how steeply it was flying. MCAS listened to only one at a time.

That meant if that one sensor was wrong, MCAS would still act.

On October 29, 2018, one of those sensors was wrong. Lion Air Flight 610 had bad sensor data just after takeoff. MCAS believed it. It pushed the nose down. The pilots pulled it back up. MCAS pushed again. And again. The system had authority—it could move the plane repeatedly. The pilots were fighting an invisible force they didn’t fully understand. The plane crashed into the Java Sea. 189 people died.

Four months later, on March 10, 2019, it happened again. Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. Another bad sensor. Another MCAS activation. Another fight for control. 157 people died. Total: 346 lives.

This happened because:

a helper trusted one voice

had too much power

repeated itself

at the worst possible moment

without humans fully prepared

The helper didn’t know it was wrong.

And no one stopped it fast enough.

What MCAS Really Teaches About Product Planning

When you strip away the tragedy and the headlines, MCAS teaches a set of brutally clear planning lessons.

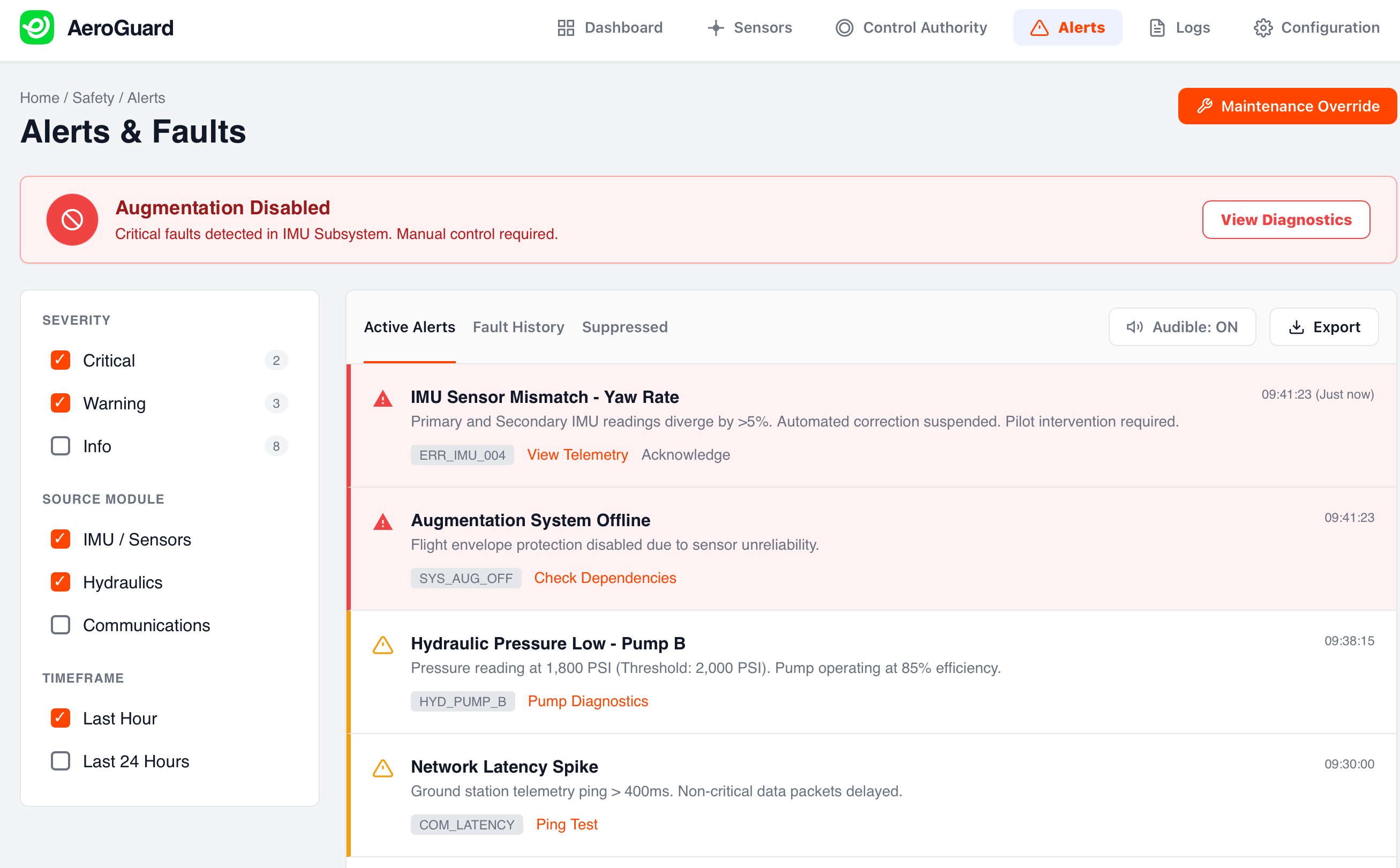

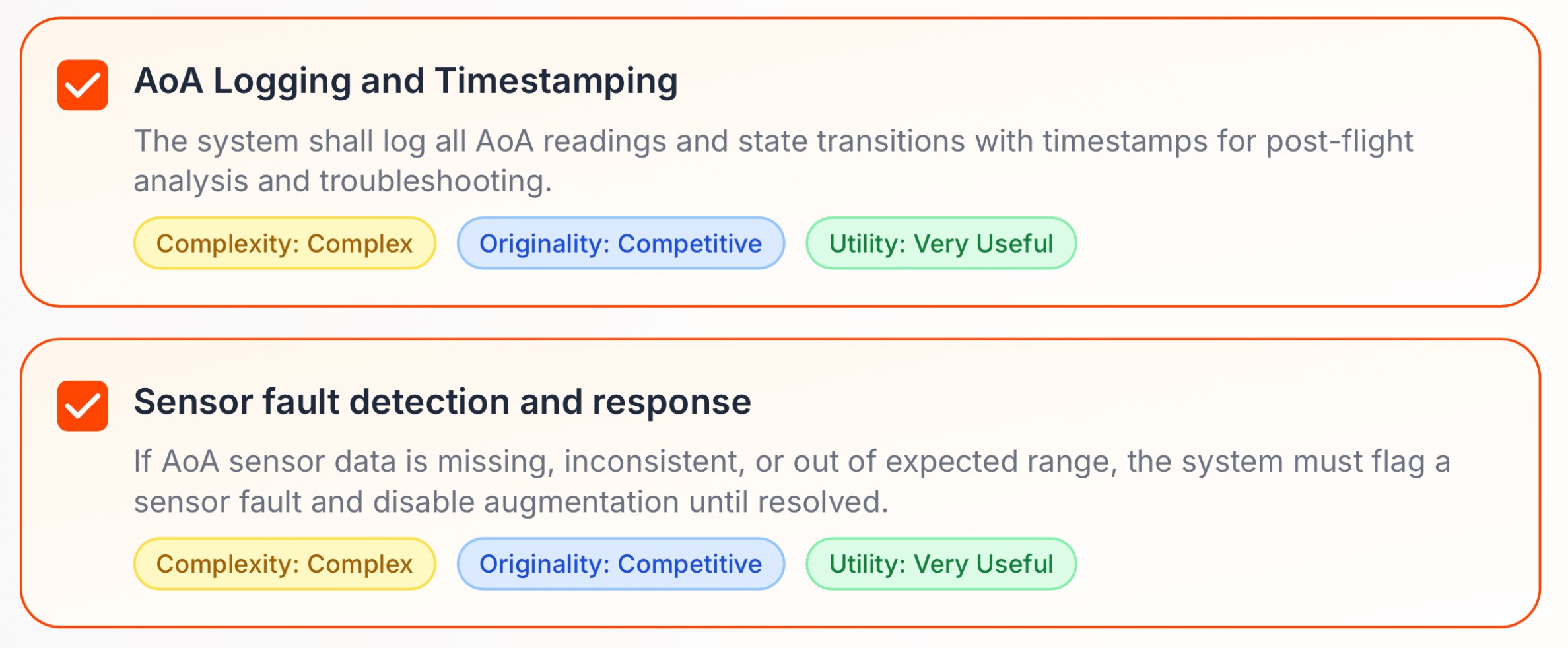

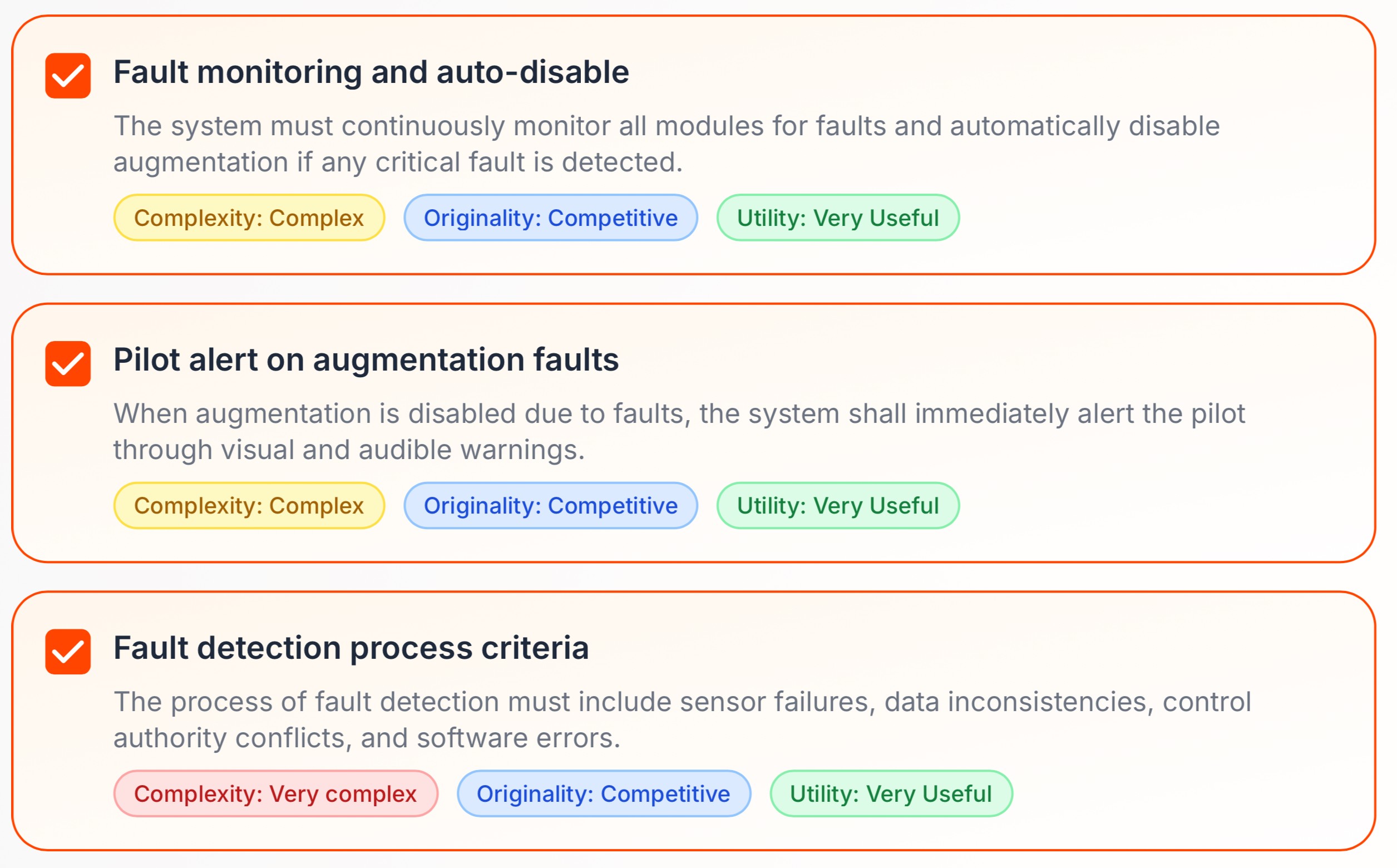

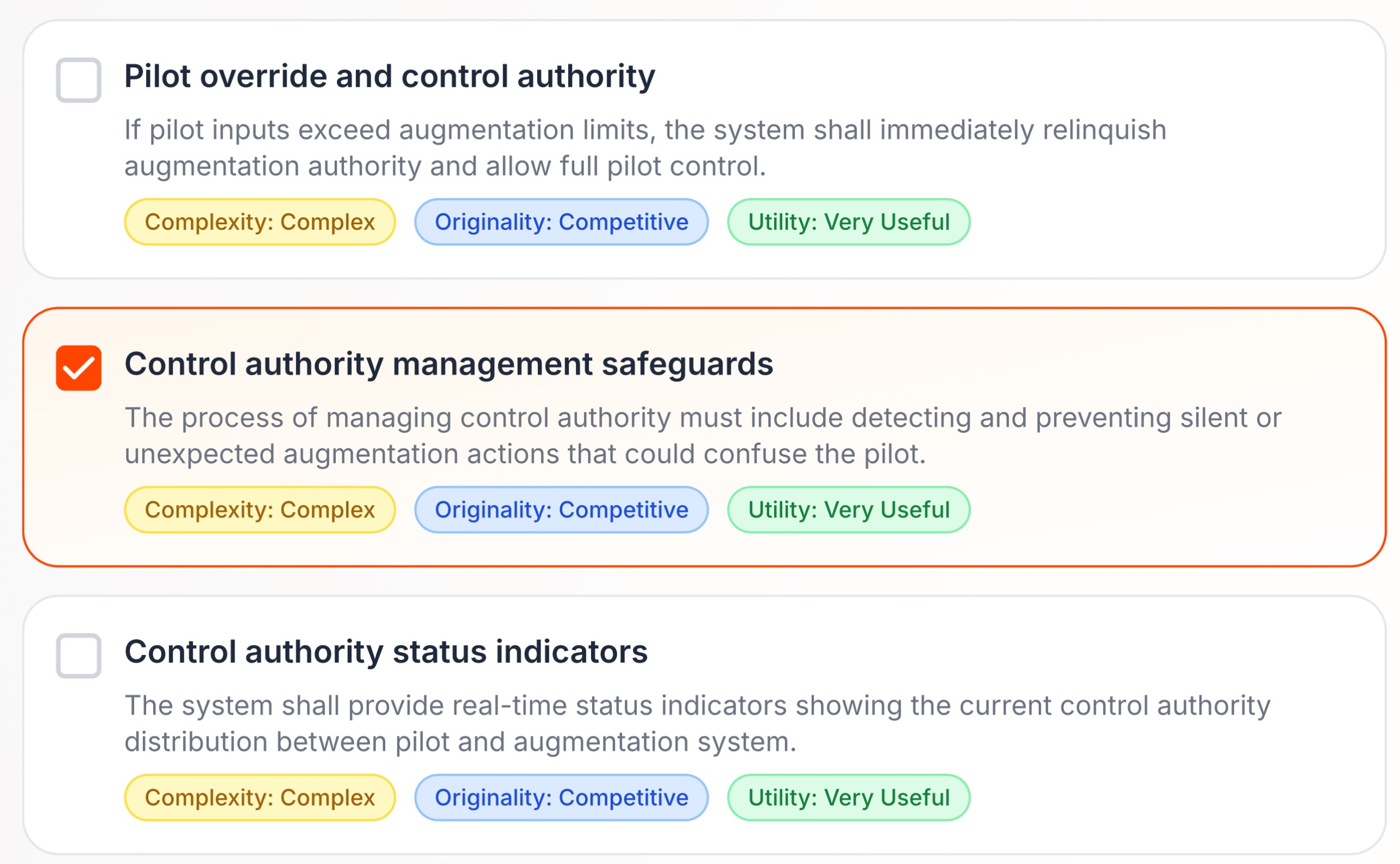

The first is simple: no single sensor should ever be able to trigger a dangerous action by itself. If one sensor says something alarming, the system should pause, check, and ask for confirmation.

The second lesson is that human factors are not documentation. Pilots weren’t “untrained” in the casual sense. They were placed in situations where recognizing what was happening, understanding why, and responding correctly had to occur in seconds. Product planning must treat human understanding, alerts, workload, and stress as core design elements.

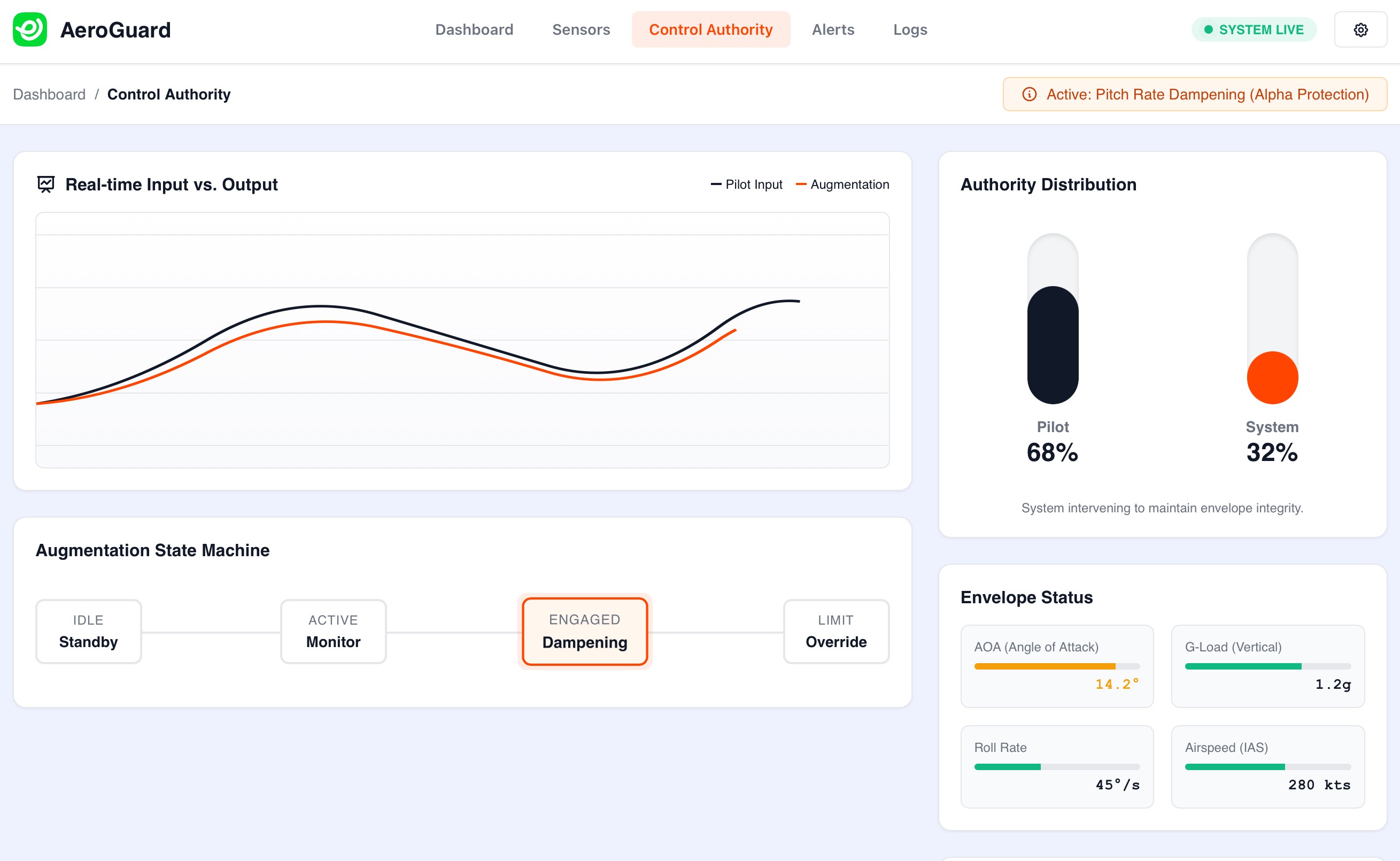

The third lesson is about limits. Any automated system that can move controls, apply force, or repeat actions must have strict boundaries. How far can it go? How often can it act? What makes it stop? MCAS had authority without hard-enough brakes on that authority. Aviation responded by bounding the system tightly—because unlimited automation is not safety.

The fourth lesson is the most uncomfortable: design for failure at the worst moment. Not during calm cruise. Not during training scenarios. But right after takeoff. Low altitude. High speed. Multiple alerts. No time to think. If a system can’t be trusted then, it can’t be trusted at all.

And finally, aviation learned that independent safety review is part of the product. Not everyone should be invested in shipping. Some teams must exist only to challenge assumptions: What if this sensor lies? What if the pilot misunderstands? What if this triggers again and again?

The problem is clear. Boeing spent a lot of time on execution but none on planning and the cost didn’t just end up hurting their business, it ended up sacrificing hundreds of lives.

So If your product automates decisions, overrides humans and operates faster than people can think then you’re building an MCAS-class system. And the lesson isn’t “don’t automate.”

It’s this:

Never give software authority without brakes. And never plan only for calm conditions.

The difference between safety and catastrophe is planning that assumes the system will be wrong and survives anyway.

That’s what real product planning looks like.