Scenario Planning for the AI-Regulated Future: How 2026 Product Leaders Stress-Test Ideas Before Reality Does

The next generation of product failures won’t come from bad UX. They’ll come from unmodeled shocks.

Yashika Vahi

Community Manager

Table of contents

Share

The New Reality Nobody Planned For

If you’re trying to launch a product in 2026, forecasting its failure should be your top priority to ensure its success remains stable in the ever evolving and unpredictable market of today.

Although our self-dignity would like us to believe it, products don’t fail because users hate them, they fail because something unpredictable happens (that wasn’t originally part of the roadmap):

An AI regulation reclassifies your feature as “high risk”

A foundation model’s pricing changes overnight

An API you depend on throttles usage

Your AI output suddenly requires explainability you never designed for

A platform policy bans a workflow your product assumed forever

Most teams still plan as if the environment is stable.

But It isn’t.

AI products exist inside volatile systems: regulatory systems, infrastructure markets, model ecosystems and platform governance layers.

If you don’t plan for shocks, your roadmap is already outdated.

The Shift: From Feature Planning → Failure-First Scenario Planning

The best teams in 2026 don’t ask:

“What should we build next?”

They ask:

“What breaks this product if the environment shifts?”

They model negative futures before optimistic ones.

They stress-test ideas against:

Regulatory shocks

What if this feature suddenly requires auditability, logging, or consent flows?

Cost volatility

What if inference costs 3× in six months?

Model instability

What if accuracy drops or hallucinations spike?

Platform risk

What if our core workflow violates a policy update?

This isn’t pessimism.

This is survival planning.

A Real-World Example: Air Canada’s AI Chatbot

Air Canada learned the hard way that an AI chatbot isn’t “just UX.” In 2024, Canada’s Civil Resolution Tribunal ordered the airline to compensate a passenger after its website chatbot gave incorrect information about bereavement fares. The chatbot told the customer he could buy a full-price ticket and later apply for a bereavement refund—something Air Canada’s actual policy did not allow. The airline argued that the chatbot was not authoritative and that customers should verify information elsewhere on the site. The tribunal rejected this outright, ruling that Air Canada was responsible for what its chatbot said, just as it would be for any content published on its website. The result: a finding of negligent misrepresentation and a mandatory payout. The message was clear—“the bot made a mistake” is not a defense.

For product teams, this case permanently changes how LLM features must be planned. A chatbot answer is not “friendly copy”; it is a regulated promise surface. If your product allows an AI system to explain policies, prices, eligibility, or entitlements, that output must be treated like a safety-critical interface. That means retrieval-only answers from a single source of truth, hard refusal boundaries when confidence is low, logged sources for every response, and clear escalation to humans when ambiguity appears. Air Canada didn’t fail because it used AI—it failed because it planned the chatbot as a convenience feature instead of a binding product commitment. In 2025, any team that doesn’t design LLM UX with this level of rigor is not experimenting—they’re accumulating legal and reputational risk.

The Insight Most Teams Miss

Scenario planning is not about predicting the future.

It’s about making sure your product doesn’t collapse when the future disagrees with you.

Before a single line of code is written, the strongest teams in 2026 run a very specific kind of planning work. It happens before roadmaps, before specs, before tickets. And it’s ruthless by design.

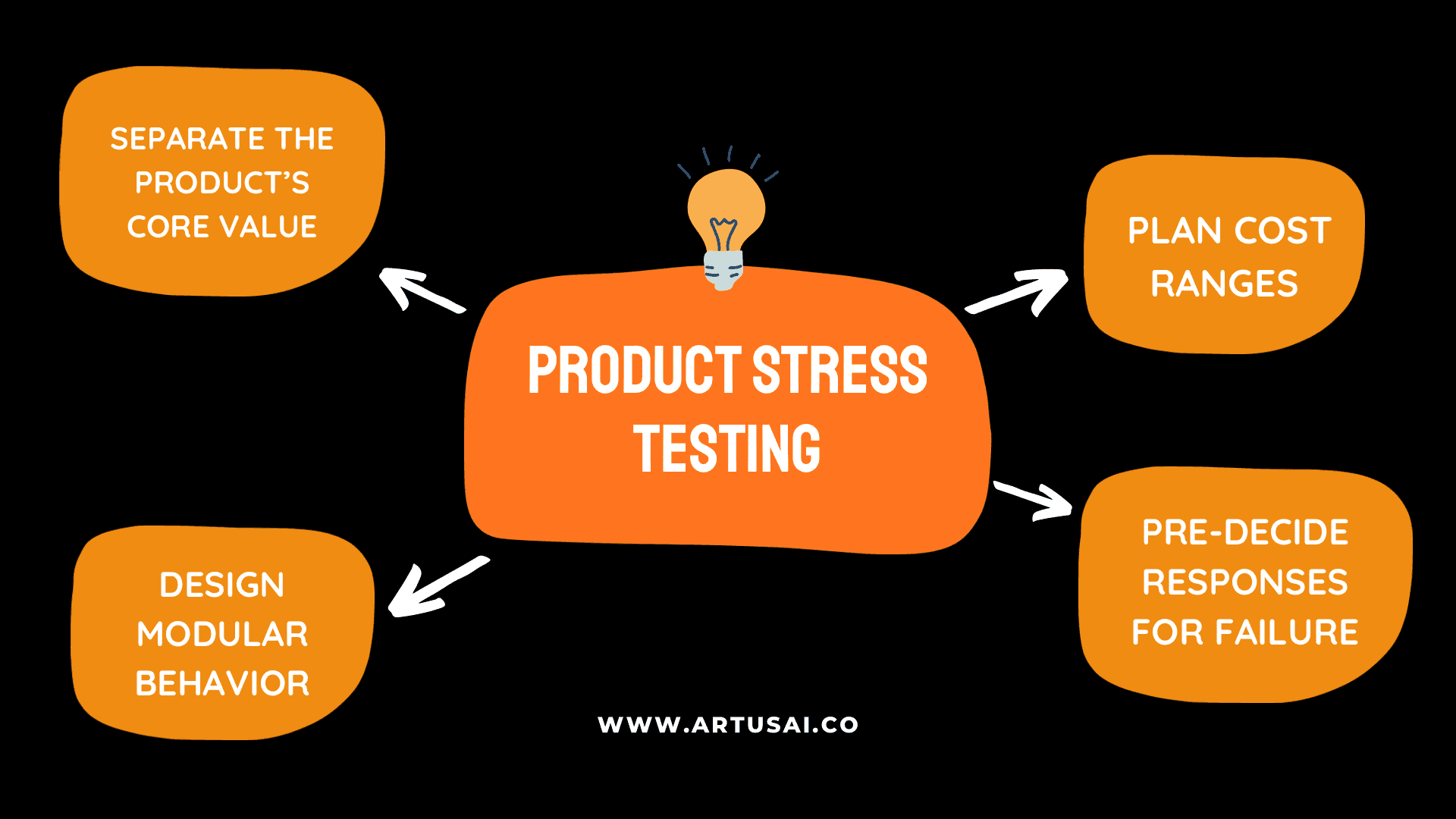

The first thing they do is separate the product’s core value from everything that could break it.

Core value is the smallest outcome the user actually cares about—not the tech, not the model, not the platform. Everything else is treated as a dependency. If a product can’t clearly answer “What still works if X disappears?” it’s not ready to be built.

Next, they map failure paths instead of happy paths.

Not “how the user succeeds,” but “where this product could realistically fail.” Regulation tightens. Costs spike. An API gets restricted. Accuracy drops. A feature becomes legally sensitive. Each of these is written down as a concrete scenario, not a vague risk. The team then asks one hard question for each: Does the product still function in some reduced but meaningful way? If the answer is no, that dependency is too deeply embedded.

Then they design modular behavior on paper.

This doesn’t mean architecture diagrams or microservices. It means deciding, during discovery, which parts of the product must be switchable, throttleable, or removable without killing the experience. If a feature can’t be turned down, turned off, or rerouted, it’s a liability—not an innovation.

After that, they plan cost ranges, not fixed budgets.

AI products don’t have stable economics. So instead of assuming one price or one margin, teams define three operating modes: normal cost, high cost, and worst-case cost. They ask: What does the product look like in each? If the answer is “unshippable” in any mode, the plan isn’t done.

Finally, they pre-decide responses. Not in code, but in intent.

If regulation changes, what mode does the product enter? If cost doubles, what feature degrades first? If a platform changes terms, what value remains? These decisions are made calmly, early, and written down—so the team isn’t improvising under pressure later.

Conclusion

This is why strong teams don’t panic when the environment shifts. They aren’t scrambling to react or reinvent the product under pressure—they’re simply executing decisions they already made during discovery. They didn’t guess which future would arrive, and they didn’t bet everything on one outcome. Instead, they designed the product to remain useful, defensible, and viable across multiple possible futures. That is what real scenario planning looks like: thinking it through early, before the roadmap is locked, before a single line of code is written, and long before any damage is done.