What If Your Product Could Predict Its Own Collapse?

How Artus Planned a VR Headset by Exposing Risks, Weak Points, and What to Kill Early

Yashika Vahi

Community Manager

Table of contents

Share

What If Your Product Could Predict Its Own Collapse?: Inside the VR Planning Experiment at Artus That Designed the Roadmap Backwards

We didn’t set out to “talk about better planning.”

We wanted to answer a harder question:

How far can a product planning team get — in one session — before engineering touches anything?

So we opened Artus, created a project called “Next-Gen VR Headset,” and forced ourselves to do what most teams avoid:

Discover the risks, constraints, trade-offs, and failure modes before anything is built.

What came out wasn’t a moodboard or brainstorming doc. It was a full, execution-ready blueprint a VR company could hand to engineering tomorrow with clear personas, friction maps, feature logic, constraints, and risk sequencing.

This article breaks down how we got there, why we made the choices we did, and why this method eliminates 6–12 months of rework that kills most hardware products.

To start off the experiment, we use a basic prompt to let us Artus know we wish to create a VR Headset.

We begin with the most honest product definition possible:

We don’t know what this headset is yet.

No features.

No specs.

No imagined UI.

No “all-in-one” promises.

2. Personas Built Around Pain, Not Demographics

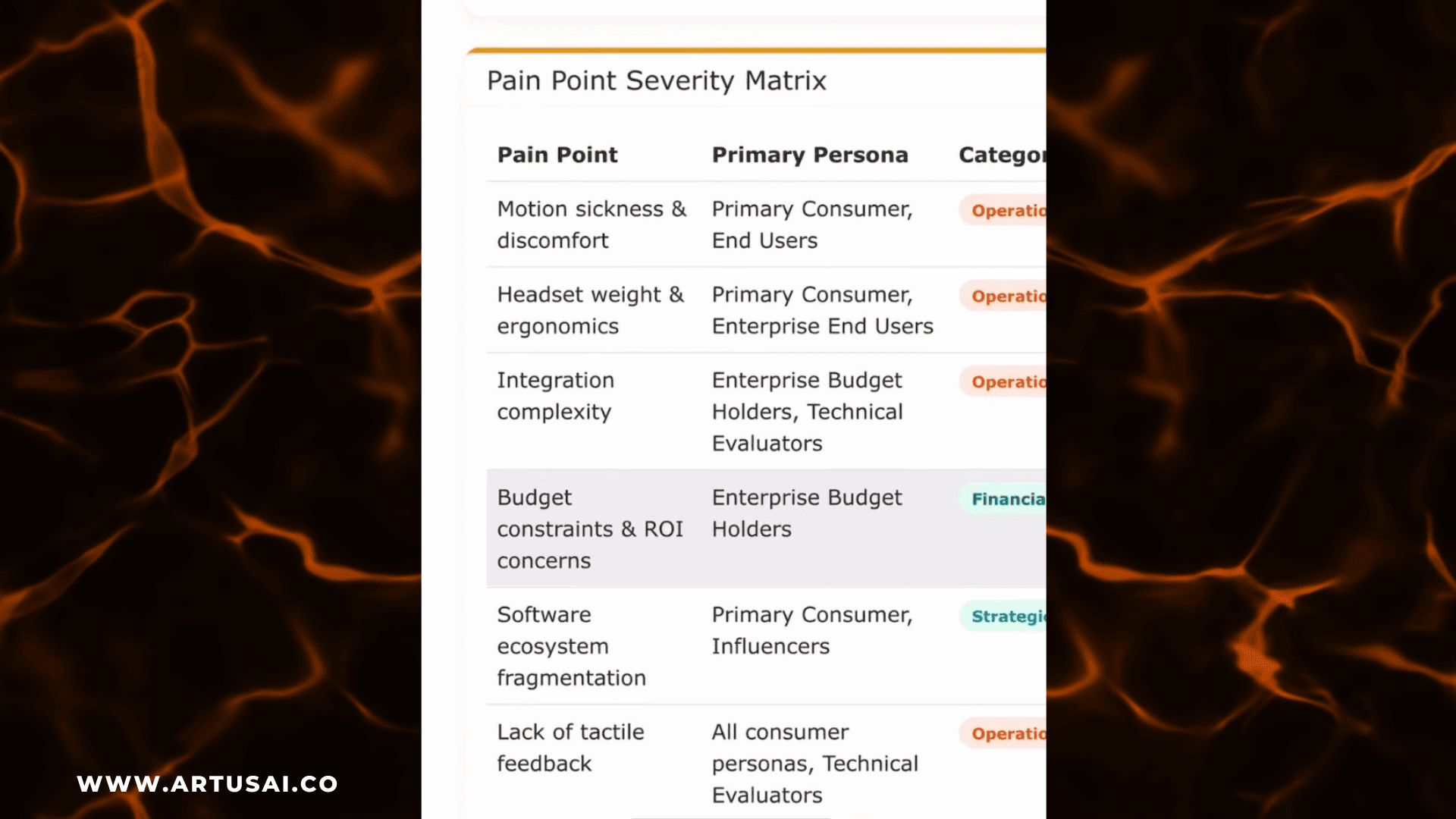

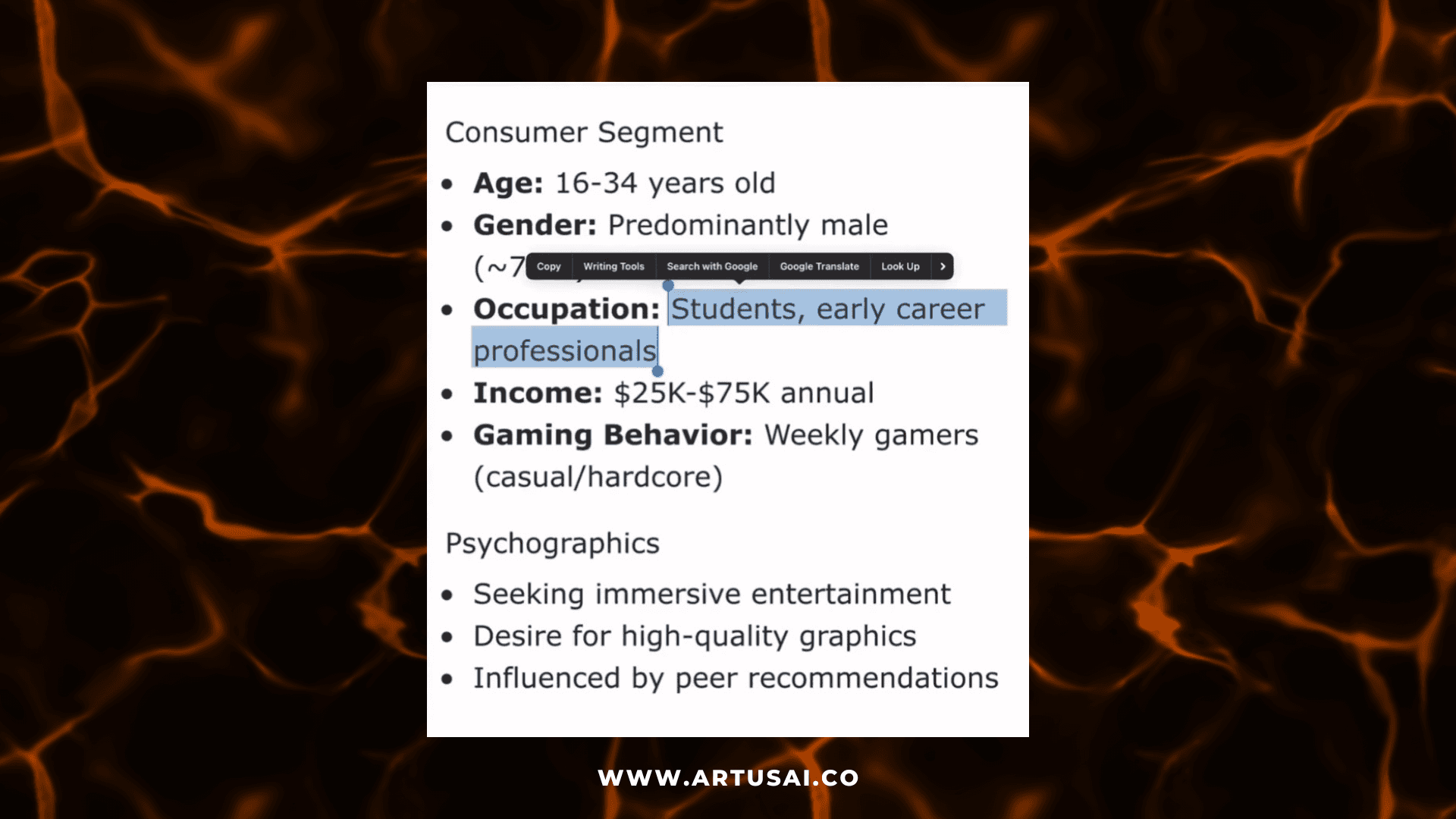

Instead of checking the Artus generated extensive market research for persona demographics (“18–35, tech-savvy, gamer”), we check the pain points first.

These are the four that emerged:

1. The Motion-Sick Newcomer

Gets dizzy within minutes

Can’t tolerate latency or aggressive movement

Leaves VR and never returns

2. The Overloaded Creator

3D modeling, designing, or prototyping in VR

Loses flow state switching apps/modes

Needs clarity, predictability, and focus

3. The Budget-Constrained Student

Wants immersive learning and collaboration

Needs affordability + comfort for daily use

Can’t justify “premium discomfort”

4. The Long-Session Power User

Hours of gaming, work, or training

Neck strain and heat are the session killers

Quits because of physical fatigue, not boredom

Artus clusters these into a few brutal truths:

People don’t abandon VR because it lacks features.

They abandon it because it’s uncomfortable, disorienting, and cognitively overwhelming.

This reframes what the product is actually solving.

3. Feature Selection: Only What Reduces Real Pain

From that point, every feature had to justify its existence by addressing real pain — not by sounding futuristic.

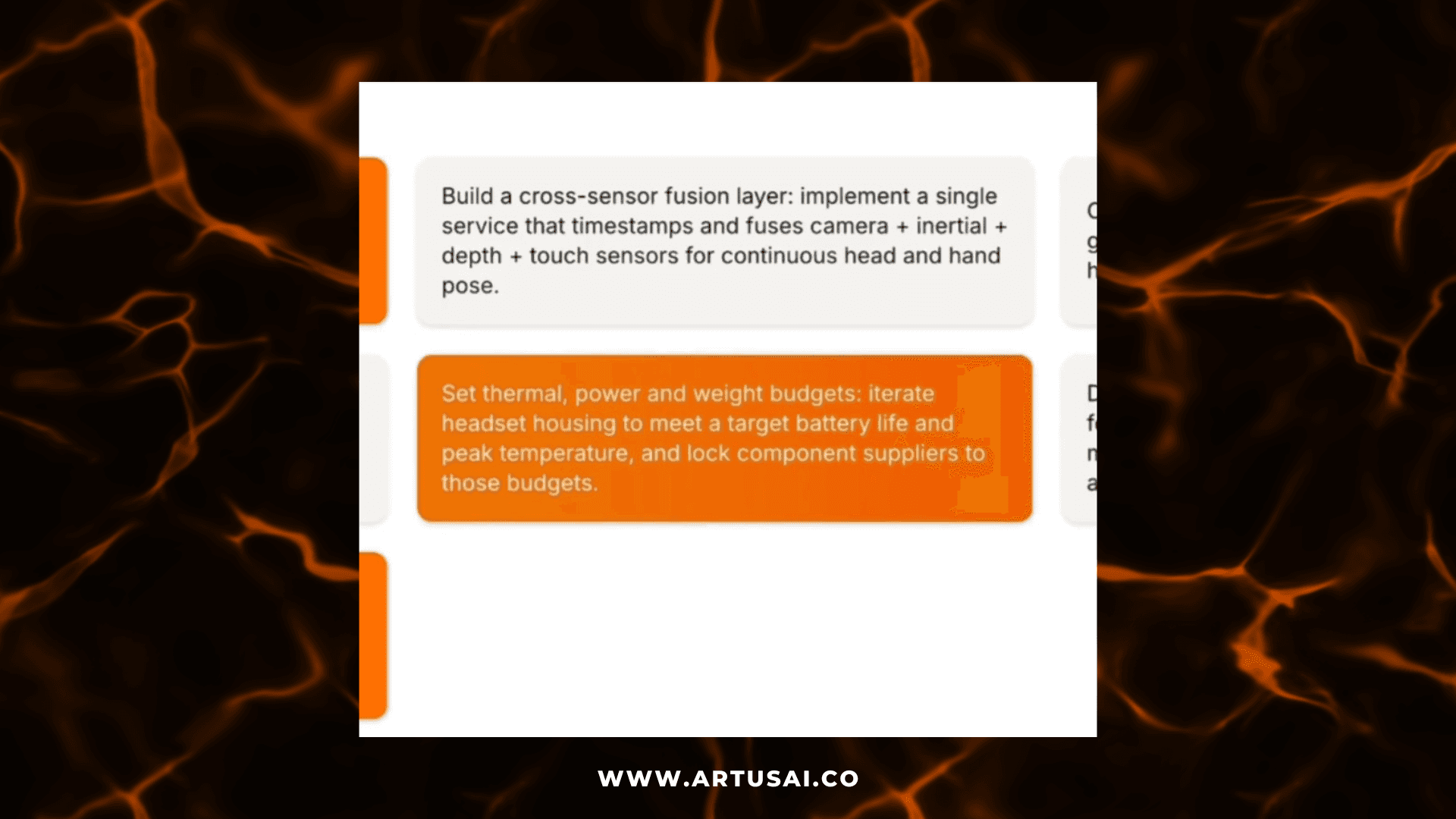

For comfort, we committed to strict weight limits, balanced distribution, and breathable materials because every persona, regardless of use case, quits when their body hurts. For tracking stability, we established a tight latency budget and reliable head and hand tracking, designed specifically around motion-sickness triggers.

For the system interface, we prioritised predictability: shallow menus, consistent states, and no ambiguous gestures. In VR, predictability beats futurism every time.

And for creators, we introduced seamless context switching so they could move between building and viewing modes instantly, keep reference materials always within reach, and rely on session recovery that protects their flow state.

4. What We Cut (Ruthlessly)

During ideation, Artus pushed us to remove anything that didn’t reduce pain. Hand-gesture navigation, AI-generated ethereal worlds, hyper-customizable avatars, and world-jumping interfaces were all cut. These ideas weren’t wrong — they simply didn’t remove discomfort, confusion, or cognitive load. They could exist later, but they had no right to exist now.

5. Modeling Failures Before They Happen

Instead of assuming the device “just works,” we defined it by how it would behave when things inevitably break.

We examined what happens when tracking drops in the middle of a session, when a controller disconnects, when the battery dips below a threshold, or when a user needs to pause instantly. For each scenario, Artus required us to specify what the user sees, what system state is saved, and how quickly the headset recovers.

This became the headset’s true personality — not its demo reel, but how gracefully it handles failure. Great products are not defined by their best moments but by their resilience during their worst.

6. The Outcome: A Complete, Execution-Ready Blueprint

By the end of a single Artus session, we were left with a VR headset concept shaped entirely around comfort, clarity, predictability, and user survival.

We had personas built from frustration curves rather than demographics, failure behaviours that made the system trustworthy, constraints that prevented unrealistic design, and a risk-ordered roadmap that engineering could begin tomorrow.

This was not a concept video or speculative design.

It was a pre-mortem in product form: a blueprint that already knows its own risks and weakest points.

A VR company could hand this document to industrial design, engineering, UX, or marketing, and every team would understand exactly why each decision exists. There would be no guesswork, no contradicting opinions, and no forgotten assumptions about “what problem we were solving.”

The Real Discovery

We didn’t just plan a VR headset.

We proved that:

A product can know its constraints, risks, failure states, trade-offs, and user abandonment triggers before a single line of code is written.

That’s what Artus does.

It turns the messy beginning of product development into a full-stack, risk-aware blueprint

so teams start execution prepared, not hopeful.